- Home

- Nicola Morgan

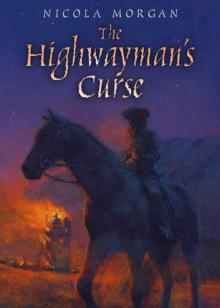

The Highwayman's Curse Page 12

The Highwayman's Curse Read online

Page 12

Iona came from round a corner, walking towards the place where the cows were. She wore a dark green skirt and bodice, a clean fawn-coloured apron round her waist. She did not see me there and I simply watched her as she took a slim, bendy stick and flicked it at the cows, driving them expertly into the yard and towards the byre. She made clicking noises with her tongue, and they seemed to understand where she wished them to go. I watched her guide them into the byre.

Wishing to talk to her, I hesitated for some moments, then went after her. As I reached the doorway, my shadow fell across her line of vision, and she looked up. For a moment, there was nothing, and then came a small smile, though perhaps a worried one.

“May I watch?” I asked. I did not particularly wish to watch. I wished to speak to her, but I did not know quite how to begin.

She nodded.

The farm cat, a sleek ginger creature, well fed on mice and birds, stirred from its place on a patch of straw warmed by the rays of sun through a window. It got to its feet, stretching, and came to rub itself against Iona’s feet.

Reaching for the small stool, she settled it behind her, positioning herself close to the larger cow, spreading her skirts so that her feet were wide apart. The beast towered above her, its bony rump swaying slightly. With expert hands she grasped the udders and began to pull downwards, one hand at a time, and within moments spurting streams of milk fell noisily into the bucket. Rhythmically she did this, leaning forward, her hair like an armful of autumn bracken hanging down her back, loosely bound in a piece of cloth.

“There is little milk left,” she said. “Her calf is growing older.”

“When will the calf produce milk?”

She laughed. “Never! It’s no’ female!” My foolishness made me blush. “He will go to market later, for meat. And then we can buy another cow in calf or we can get this one wi’ calf again and sell her milk.”

She squirted a little milk at the cat. It jumped, but immediately set to licking the creamy liquid from its chest, purring as it did so.

“Last night,” I said, to change the subject, and because I had no wish to talk of cows. “I need to know everything. Otherwise I cannot help you.”

She looked fearfully over my shoulder. “Shh!” she whispered.

“There is no one here,” I assured her. Bess and Jeannie had gone to the nearest town – Wigtown, they said – to buy provisions, with Billy driving the cart. Jock was resting, his head paining him again. I could see the others outside, two mending the roof of the chicken shed, another chopping logs, another making rope. Calum was sharpening knives on a whetstone near the yard entrance. I remained standing in the doorway, where I could see them.

“I must know. If I am to keep your secret. Who is the boy and why can you not tell anyone?”

She hesitated in her milking. The cow turned round to look at her and stopped chewing its cud. She resumed. The cow returned to its chewing. Iona did not speak, though she opened her mouth to do so but perhaps could not find the words. “Where did you meet him?” I asked, thinking to loosen her tongue with a lighter question.

“Some months past, when I was in the town. It was no’ difficult and sometimes I would see him at the market. I had more freedom then and it was no’ difficult, until the trouble grew worse between the Murdochs and our family. And now, we meet in secret, and not often.”

“And would your family have been so angry that you loved a boy?”

She looked up then and something tightened in her face, though she continued with the milking.

At that moment, I knew that I was right. “He is of another religion, is he not? A Catholic, or from the church of bishops – I have forgotten what you call it.”

She nodded, biting her lip. “The Episcopalians,” she muttered.

So, I had been correct. I wished to say it did not matter. But I knew enough to know that it mattered here. I could only try to persuade her to forget him.

“This will bring only danger and sadness,” I began. “Think how angry your family will be. It would be better for you to forget him.”

She shook her head. “But I love him,” she said, her voice somewhat petulant.

“You can love again.” What did I know of this? Of course, I had felt my heart beat faster at the sight of a pretty girl, a stirring in me at the call of red lips or soft eyes, but I had not met a girl who destroyed my reason as love is supposed to do.

But Iona had something else to say.

“There is more. Ye wished to know it all. And when ye hear it, ye’ll believe Old Maggie – I am cursed.”

I waited.

“His name is Robert Murdoch. He is Douglas Murdoch’s son.”

Then indeed did I feel the chill of fear. Though I did not understand fully the intricate hatreds of religions, the wrongs dealt through the ages, the pendulum of punishment and anger, yet I knew well the warring between these people and the Murdochs.

Now, too, I feared for myself. For if Jock and Thomas and Red and the others later discovered that I had known, that I had shielded her, what then would happen to me?

Yet, how could I tell them? What might they do to Iona?

There was no choice: I must hold this knowledge to myself.

What if Douglas Murdoch learnt of it? Perhaps he did not hate her religion as much as her family hated his? After all, he had planned to take her, for what purpose I knew not. It might be better for her to be taken by them. Could she then live with them, perhaps marry this lad and be happy?

Sensing a glimmer of hope, I asked her. “If Douglas Murdoch knew of this, what would he do? Perhaps he would not be as angry as your father would.”

She stared at me. “Douglas Murdoch would rather his son were dead than wi’ me! Ye have seen my father and my uncles when his name is mentioned. ’Tis the same for them. And worse, because he is rich and to him we are nothing more than dirt. He would take me for his servant, no’ his son’s wife, and it would go ill wi’ me. So they must no’ hear of this. Ye must tell no one! Promise me!”

“I will tell no one,” I promised, quietly. “But they killed your great-grandfather, the old shepherd, did they not? Can you forgive him for that?”

“Robert hates their violence,” she retorted. “As do I hate my family’s violence. He had nothing to do wi’ the killing, and if he had, I wouldna forgive him. I loved my great-grandfather. He loved me, and he always tried to stop Old Maggie railing at me. Now he’s gone and no one will take my side.” She wiped the back of her hand across her eyes and took a deep breath.

“Now, tell me I am no’ cursed!” she said, her eyes bright. She stared at me with defiance. I said something – mere words. Clumsy, muttered nothings. She just tightened her lips and looked away with a shrug.

Was she cursed? Perhaps so. And in truth, she believed herself cursed. Her family, too, seemed to think it.

A thought came to me. These people trusted so strongly in the curse, that they were merely waiting for something terrible to happen to Iona, the only girl left in the family. They did not wonder if it would happen, but just waited for when it would. But is the future set down already? If it is, then why do we concern ourselves with how to act or what is right?

If fate, or God, has already decided what will happen, then can anyone be blamed for anything?

This could not be the way of it. God judges us on what we do – the Bible had taught me so. But if the future is set down, we cannot choose what to do. And if we cannot choose anything that we do, how can God rightly judge us?

And if the future is not laid down, then a curse can have no power. If fate had not decreed that Iona would suffer a terrible fate, then she might not suffer a terrible fate.

Perhaps a curse only has power if we believe in it. If we fight against it, we may turn the future to a different outcome.

Perhaps that is what hope is for. I knew the story of Pandora. When disobedient, curious, interfering Pandora let all the evil into the world by mistake, only Hope was left.

&

nbsp; And so I could hope. But I could act, too – act to protect Iona from danger. Because it seemed to me that Iona, by falling in love with a boy from a different religion, was the only one not poisoned and trapped by endless hatred.

This was something I could do to fight against all that Old Maggie stood for: hatred, anger and revenge. And in their place put something better.

Chapter Twenty-Nine

The rest of the day passed without further event. There was no chance for me to speak alone with Bess – always she was with Jeannie or Old Maggie, helping with chores. There was not quite a coldness between us. She smiled when she saw me. But she was busy and did not seem to need to speak with me. It was as though she was settled, in a way that I was not.

What did I wish to say? I cannot be sure. Not to tell Iona’s secret, though it was indeed a heavy burden to bear. If I am honest, I know not what Bess’s response would have been. She cared little for Iona, perhaps because the girl showed no love for Old Maggie. But Old Maggie showed no love for the girl, nothing but crazy words and fearsome curses – how should Iona have acted differently?

And Bess’s admiration for the old woman was something I could not share. I pitied her suffering, but that was all.

I wished Bess did not admire her so. I wished more than ever that we could both go away. But that could not be, not now, for I could not leave Iona to her fate – though I knew not how I could help her. And Bess, it was clear, would not come away.

That night, too, was peaceful enough, with no intrusions, no alarms.

That following night, the Wednesday, however, another cargo was expected. By now I had picked up smatterings of conversation and understood something of what would happen. Calum would go to a place on the cliff and watch for a particular light over the water. This was the sign that the cargo had been offloaded from the cutter sailing from the Isle of Man, or Ireland, and onto a smaller boat. This boat would be manned by two seamen from the cutter, who were in Jock’s pay, and would be rowed to our cave at high tide. When Calum saw the signal, he would run back to tell us and we would go down the tunnels as before, and collect the goods when the tide started to fall and the cave would be safe from ambush. Next day, the goods would be taken to nearby towns and sold by Hamish. The blind minister was a useful way to avert the attention of the authorities. No exciseman would dare search a coffin for smuggled goods, and he always had a coffin with him. And Hamish did such things as taking the money to the seamen and learning when the next ship might be passing.

During the Wednesday afternoon, I began to have a sense of the work these people must do if they were to eke a living simply from the farm. It was difficult land, in places soggy marsh, in others stony and fit only for gorse. Mouldy told me that the best and most fertile land was enclosed by Douglas Murdoch’s walls, that his cows and sheep grazed the richest grass and his fields grew the sweetest clover and flax for linen. Murdoch even had his own linen mill, though he paid his workers little.

We had to drain a piece of marshy ground for planting. After paring the surface with a hand-plough, we had to divide it into runrigs – so that the water could run along the channels and some kind of crop be grown along the ridges. Quickly, my back became stiff and painful, but if I had thought we could rest when this was finished, I was wrong – we must now dig the last remaining winter turnips from the ground – soft, thin things they were, but better than nothing with all the fodder now gone.

So it was with aching limbs that I went to sleep that night, not heeding the noise of Old Maggie snoring, the rustling in the thatch, or the wind snarling at the shutters.

Chapter Thirty

As we had been warned, we were woken in the middle of the night. It was Billy who came banging on our door and led us over to the main cottage, lighting the way with a burning peat torch. Lamplight filled the dwelling and faces glowed. As before, Jeannie gave us food and drink. There was excitement in the air and I felt a sense of why these people did what they did. This was better than farming the waterlogged land around their home. Highway robbery is little different from smuggling, perhaps, and something thrilling rushes through the body when adventure beckons. My doubts slunk to the edges of my mind and I threw myself into the action.

No fear did I feel as we climbed down the rungs and then along the steeply sloping tunnel. It was high tide again and the waves shot fountains into the air as we leapt across the churning passageway. We climbed the few steps and then leapt across again. This time, I did not slip and I had no need of helping hands to pull me onto the ledge. I felt Mouldy slap me on the back. Even Red split his face into a grin on my behalf.

Jock did not come with us this time. Jeannie and his sons had persuaded him not to. I think his head pained him again. Certainly, he pressed his hand frequently to his forehead and seemed not to wish to stand. There was no colour in his leathered face.

Soon, we were in the cave again, a little out of breath, sweating lightly. I looked at Bess and she grinned at me, her black eyes sparkling, cheeks pinked, lips a little apart. Her thick hair was tied behind her with a red kerchief, and shone in the dancing light of the peat torches.

Now it was time for her to squeeze through the narrow space at the bottom of the steps. No one spoke; there was no need. She dropped to the ground, pushed her hands through the hole and wriggled quickly out of sight. A few moments later, she called that she was through. We sent the ropes after her.

As before, we heard the noise of her opening the first box, the lid splintering. As before, we heard her voice as she called out what she had found: malt and bundles of lace this time. As before, we felt the tug when the first bags were filled, and we pulled the bags towards us.

Then, horribly, echoing through the caverns and crevices, caught up in the roaring and crashing of the waves, came a scream. And then another. Some scuffling, and another smaller scream.

Chapter Thirty-One

At first, I could not move. No words would come. We all stared at each other, eyes wide in the torchlight, the shadows casting our faces into the shapes of ghouls. What had happened? My mind fought to make sense of it.

I crouched on the ground and shouted through the opening. “Bess! What has happened? Bess!”

Then her voice, brittle with panic. “A snake! I’ve been bitten by a snake!”

“Tell her to take hold o’ a rope and we will pull her back through the tunnel,” said Thomas.

But Bess’s voice came back, weaker now. “I can’t see, Will. The torch fell. Help me! I can’t see…”

“Bess! Listen! You must tie the rope to your wrist and we will pull you.”

“Will! I am … I feel … dizzy. I can’t…” And then there was a scuffling sound, a soft thud, and silence. I had not thought a snakebite to be so dangerous, so fast acting. Perhaps she had fallen into a faint from the fear.

I pulled my jacket off and dropped to my hands and knees. Already, my chest felt tight. Already, my breathing was faster. I must somehow squeeze through that narrow space. It could be done. Bess had not found it difficult – but I was somewhat broader. Could I do it?

There was no choice. Stretching my arms in front of me, I plunged into that dark space. At first, I could see nothing. Utter blackness pressed down on me. The rock felt cold against my hands as I pulled myself along, using my toes to push. My face was inches from the tunnel floor and only inches more separated the back of my head from the rock face above me.

Panic rushed through me and I struggled for breath. At that moment, some dust or grit entered my mouth and I coughed. There was no room to draw enough air and, as I choked, I felt the rock close in round me, darker, colder, harder, heavier. I needed to push myself upwards, to give my chest room to move, but I could not do so, for above me was rock.

The thick rope underneath my body lay still and useless, pressing on my ribs. I pulled myself forwards with my hands and pushed with my feet, scraping desperately on the floor of the tunnel. I must move faster. Still there was darkness in front of me, d

ust in my throat, no room for my shoulders to move.

Now the passage narrowed further, sloping downwards. Surely my shoulders could not go through this space? My feet could get no purchase now on the grit and dust. I felt around frantically with my fingers, looking for something to grasp, in front of me, or to the sides, or above. Yes! A rocky overhang. I gripped it hard and tried to pull. With my arms outstretched and my shoulders squeezed together, I thought now that I could not move, or even scream.

I was stuck. My eyes were wide open, but only speckled blackness spun round me. For some moments I felt that I was spinning too. No longer could I feel the hard walls, the rocks pressing against my body; no longer could I smell the dust, taste the grit between my teeth. My body softened. The black became red, rushing across my eyes. Fear was still there, but it seemed somehow to matter less. I think if this is how we die then death is not so fearsome after all. I felt my mind spin, closed my eyes and let myself slowly drift. No longer did I need any air.

“Will!” From far away, I heard my name called. “Will! Please!” It was Bess, her voice weak. And now terror rushed back and with one last effort, I pulled, squeezing myself past the narrowing until the tunnel opened out – a little, but it was enough. I could breathe again. Now my heart beat fast, as I sensed how close I had come to death, how nearly I had given in to it.

Forgetting that there would be a drop at the end of the tunnel, I fell headfirst for a few feet, my hands landing painfully on the rough rock floor. I gasped the air, fresh air straight from the sea.

The darkness here was not so deep. No moonlight shone directly into the cave but I could make out the mouth of it, see the ebony waves glinting under the waxing moon. A groan to my right told me where Bess was, but before I moved to her I heard Thomas shout to me, “Pull the rope.” This I did, and almost immediately a burning torch spiralled towards me along the tunnel. I caught it and looked around.

The Highwayman's Footsteps

The Highwayman's Footsteps Wasted

Wasted The Highwayman's Curse

The Highwayman's Curse Deathwatch

Deathwatch